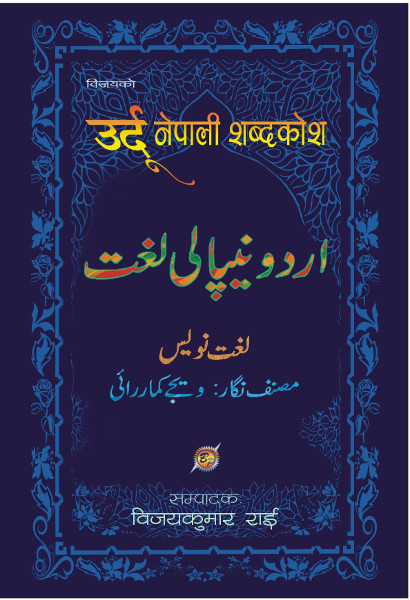

The article is a translation of the foreword provided in Urdu-Nepali Shadakosh, originally written in Nepali by Bijoy Kumar Rai. The entire foreword has not been translated, only the relevant parts have been extracted and published.

From the time I was born, and up until I grew up to become an adult, I lived in a Muslim majority neighbourhood in Darjeeling called Dr. Zakir Hussain Busty. It was the direct influence of growing up in such an environment that inspired me to write and publish this Urdu-Nepali Sabdakosh or Urdu-Nepali Lughat. It was because the language spoken by my childhood friends and neighbours was Urdu, that I felt the words that they used were native to me. A man whom I knew as Janab Zafar lived opposite to my house. With a cane always by his side, he used to conduct tuitions on Urdu for the Muslim children. When we were teenagers, we accompanied Janab Zafar and listened to ghazals by the greats such as Mehdi Hassan and Ghulam Ali. Not only Mir Taqi Mir, Mirza Ghalib and Sahir Ludhianvi, but we were also introduced to the whole symposium of Urdu poets, and were able to learn from and about them during our adolescence. The veterans of Urdu poetry in our neighbourhood used to play qawwali in their tape recorders throughout the day, it never seemed to bother me. The prosperous culture that accompanied these qawwali songs, sufi poetry, and ghazal singers have influenced me deeply; just simplifying it to influence would be lacking, within these maestros I discovered nothing less than miracles. It now seems to me that the time I devoted to listening and reading Urdu ghazals and nazms during these forty years had a purpose, and it was to pen this dictionary, seemingly a destiny divined.

[A few reasons that have led me to work on this project:]

There is a large section within the Nepali speaking community who listen to Urdu ghazals. From the time Motiram Bhatta adopted the form and up until now, the discipline of writing ghazals has flourished. Even if people do not study them due to disinterest in literature, the advent of streaming technology has expanded its audience. The increase in accessibility of technologies like computers, smartphones and the internet has made available to the people songs, videos, and literature from several languages. Digitalisation has enabled people to instantly share these through social media platforms, furthering their audience and popularity. Internet has granted an almost free access to films, sporting events, news, e-mail and social media platforms, but its most pertinent contribution lies in providing access to documents, photos, books and magazines in handheld devices. Although these facilities exist and through a shared network are accessible to anyone may want to pursue them, many facets remain untouched due to lack of scholarly background and experience required to understand and review them. Also, it necessitates personal perseverance to make available these contents in a readable manner, ideally in the form of a book. The lack of variety and forms in contemporary Nepali literature becomes evident when compared to other languages.

Nepali language or more specifically its spoken form has numerous loan words from other languages, albeit altered with their own peculiar features. The prose or standard language used for writing in Nepal is quite different from that which is used in India, especially when it comes to the use of words. A whole segment of words used in Nepal seems to be absent from the vocabulary and writing of Indian Nepali literature due to inapplicability or incoherence. A significant cultural and literary inheritance of various communities in India including Nepali seems to include contributions from the Arabic and Persian languages, along with the systems of administration that were prevalent there in history. Words from the Urdu language which have seeped into Nepali, their prevalent use and features, has the possibility of becoming an interesting scope of study.

Loan words from other languages in construction of the Nepali language has enriched the language and made it more prosperous. Cumulatively there are more than twelve hundred words borrowed from Arabic, Persian and Turkish in the Nepali vocabulary.

Urdu Language and Us

Introduction

Amongst the most prosperous languages in the world, Urdu has carved a niche for itself. As citizens of this nation, we must be proud that a language such as Urdu emerged in our lands. The history of our nation which is defined by multiple communities, rulers, ways-of-life, cultures, religions, art forms, languages and a vast literature led to the development of the Hindustani language. Through scholarly sources it is ascertained that– overtime a cluster of many local dialects which emerged from older languages such as Sanskrit along with words from languages like Arabic, Persian and Turkish developed to take the form of Urdu. Hindi and Urdu are complementary of each other.

Nepali also has a close relationship with Hindi and Urdu. While Nepali and Hindi are primarily written in the Devanagari (देवनागरी) script, Urdu is also seen to be written or can be written in the Devanagari script. But when Urdu is written in the Devanagari script, almost half of the Devanagari characters remain unused because these characters or sounds are alien to the Arabic, Persian and Turkish tongue. Urdu primarily uses the Nasta‘līq (نستعلیق) script which owes its foundations to Arabic and Persian. The Turkish language defines Urdu or ‘ordu’ as a ‘king’s camp’. The language spoken in the camp by the army of a king came to be known as Urdu. The language is also called Lashkari, and has many other names such as Rekhta, Hindvi and Dehlvi. Without the verbs of Sanskrit and Prakrit, or the essential knowledge of the Hindi language, forms of Urdu writing and literature would remain incomplete. Urdu has been bestowed with the honour of being the national language of Pakistan. Among the most spoken languages in the world, Urdu [with all its dialects and counterparts such as Hindi] ranks fourth, just after Mandarin, English and Spanish.

A Long Running Relationship with Urdu

A) Historical Relationship

Around eleven hundred years ago or in the year 982 CE, a Persian book was published by the name of Ḥudūd al-ʿĀlam (The Regions of the World), it mentions traders who imported textiles and musk from the region that is now known as Nepal. There are also sources which suggest that in the year 1324 CE, the conquests by Muslim rulers extended till the outer regions of the Nepal. An old genealogy mentions that in the year 1349 CE, Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah– soon to be the first Sultan of Bengal– attacked Nepal for seven straight days. After the military campaign by Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah, many structural reforms were brought in by the Malla rulers. In order to improve administrative systems, Jayasthiti Malla introduced feudal systems which were in vogue at that time among Muslim fiefdoms and kingdoms. Their is plenty of evidence which supports the idea of adoption such as the way the Malla rulers dressed themselves, the language they used and their system of governance.

“in the year 982 CE, a Persian book was published by the name of Ḥudūd al-ʿĀlam (The Regions of the World), it mentions traders who imported textiles and musk from the region that is now known as Nepal”

At the time when Humayun led the Mughal Empire, Mahendra Malla paid tribute to the Emperor in Delhi and in exchange was granted permission to produce an independent currency. Hari Gopal Mukherjee– a numismatist who focuses on Indian currencies– has opined that currencies of Muslim rulers were in circulation inside the [now] territory of Nepal between the thirteenth and sixteenth century. During the rule of Ratan Malla, in the time between 1491–1501 CE, many Muslims are said to have come and settled in Nepal. In that period, Muslims from Kashmir also frequented the region in order to trade in Tibet. Jahangir [or Salim if you are enamoured with Mughal-e-Azam] declared the Gorkha kingdom under Ram Shah to be an independent territory. During the reign of Aurangzeb, Damodar Sen– ruler of Tanuha– granted permission to Muslims to settle in his kingdom. When Prithvi Narayan Shah attacked Makwanpur as part of his conquest, Mir Qasim– Nawab of Bengal– deployed troops in aid of Gurgin Khan [the latter lost due to unfamiliarity with the terrain]. After 1799 [Vikram Sambat], during the unification campaign by Prithvi Narayan Shah, the kingdom of Gorkha received significant aid in manufacturing weaponry from Sheikh Bajhar and Muhammad Taqi. After the advent of the Rana regime, systems and nomenclatures of administration were heavily influenced by the Persian language.

B) Cultural Relationship

Nepali community seems to have been heavily influenced by the then prevalent Mughal practices, be it in traditions or court culture. Words such as mughlaney and laurey are telling of the conditions of the community during that period. Bhanubhakta’s famous headgear or topi– the fulbutte karchobi– is a legacy of Mughal attire, same could be said for the bhadgaule topi which closely imitates vestments worn during the Mughal era. Dhaka topi is perhaps the most identifiable and popular headgear within the community. As the name suggests, its history is directly connected to the city of Dhaka which is now the Capital of Bangladesh. Influence of Mughlai cuisines on food preparation and habits is also quite evident.

From the Dhaka of undivided Bengal and then through the Bengal region, the dhaka cloth made its way into Nepal to eventually become the dhaka topi. Garments such as dhaka cholo and dhaka shawl worn by Nepali women also share the same history. Furthermore, the craftsmanship with which these garments are made resemble tailoring practices closely associated with Mughals. Budhimann Rai, my grandfather-in-law, was the representative of Kalimpong in Bhutan and a zamindar in the Jalpaiguri region. He was a shareholder– Shareholder Number 232– of a company called Dhakeshwari Cotton Mills which was set up in the Dhaka district. When the Khilji dynasty launched an attack on Bengal, the Sen and Pal dynasties were displaced and had to build their kingdoms in hilly regions of Nepal. It is believed that the dhaka cloth first arrived with them and has been suggested that after they established their kingdoms in the Palpa region, the ‘palpali dhaka topi’ gained popularity. Later, under the Rana regime, affluent women popularized dresses made from the fabric, and now has become an important cultural identifier.

“Bhanubhakta’s famous headgear or topi– the fulbutte karchobi– is a legacy of Mughal attire”

Traditional Nepali musical instruments such as the Naumati Baaja is related to Naubat instruments. These musical instruments are not confined to a few communities, and are seen being played all across the country (India). Other musical instruments have also been adopted by the Nepali community. Trends highlight a strong possibility that the weapons used by Nepalis in the time of warfare and the tools used during daily life were learned from Mughal craftsmanship.

C) Social Structures and Connections

Surnames assigned to different communities in India, including Nepali, leads to an interesting enquiry. Khawas, Rai, Hamal, Dewan, Nagarchi, Paswan, Darji and Raute are few such examples of superimposition of titles on castes and tribes, and the eventual adoption of these titles as surnames. These titles which had been bestowed for purpose of administration or occupation are derived from Urdu or its loan words. These names and titles help indicate and identify the social structures during different periods throughout history.

D) The Relationship with Language and Literature

Perhaps the most revered and celebrated Nepali poet in India, Adikavi Bhanubhakta Acharya’s creations were built with Urdu words. Nepali literature, songs, ghazals, and the language spoken by the masses is also filled with Urdu words, and these words come up quite often. So the know-how of the language from which we frequently borrow is essential, that is another reason a dictionary becomes necessary. Talking about Urdu-Neapli dictionary, it should be mentioned that an unpublished book by Jitamitra Malla– ruler of Bhaktapur (1673–1696 CE)– called Pārsīkosh is kept in the Nepal National Library. This year the centennial birth anniversary of Shiva Kumar Rai, a renowned literary and political figure, is being celebrated all across India. His writings are filled with Urdu words. Without understanding the context of these words, discussing his literary legacy would be a half-hearted endeavour is what I believe.

E) Darjeeling and Urdu Speakers

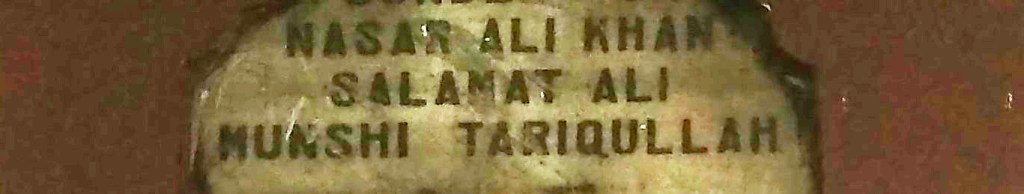

The tale of indigenous communities from the hilly regions of Darjeeling, living with and accommodating Muslim settlers, is quite old. If we look at Darjeeling’s history, at one point in time, it used to be a part of Nepal. Present findings state that the Hindu-Buddhist mandir in the Mahakal hilltop was built before 1765 CE and the Lal Dhiki Jama Masjid was built around 1786. According the medieval Indian history, Qutb al-Din Aibak– ruler of the Delhi Sultanate– had plans to invade Tibet, but his troops were unable to march upwards from the foothills. Armies of another ruler of the Delhi Sultanate, Muhammad bin Tughluq along with Ikhtiyār al-Dīn Muḥammad Bakhtiyār Khaljī initiated a Tibet campaign during the winters, and marched through Kurseong, Darjeeling and Sikkim. Legend has it that a Maulvi who was travelling with that army laid the foundation stone for what would eventually become the Jama Masjid of Lal Dikhi, locally known as Anjuman-i-Islamia. Construction for the large structure with which we are familiar was started on 1862 by Nasar Ali Khan, Salamat Ali and Munshi Tariqullah.

In the year 1865, the lieutenant-governor of Bengal approved five Anglo-vernacular schools in Darjeeling; one of these schools was the Darjeeling Zilla School (currently Darjeeling Government High School). According to ‘A Statistical Account of Bengal’ by William Wilson Hunter (Trübner and Company, London 1876), English along with Persian and Urdu were already being taught in Darjeeling Zilla School prior to 1865.

Urdu speakers who had worked in various trades and occupations influenced the writing of Nepali plays and songs in Darjeeling. The drama scene in Darjeeling begins with Atalbahadur (1909); along with English and Bengali plays, Urdu plays were also staged– Alauddin, Abu Hussain, Safed Khoon, Sunndarr Aafatt, Botahl ki Devi, Jeevaniko Dhanda Ankhako Andha, Wairam Lutaera, Layla-Majnun, Teen Dhaaray Tarrwarr and others. Urdu plays were also performed in Kurseong– Shirin Farhad, Layla-Majnun, Sultan Daku and others.

Rajib Chatterjee submitted his doctoral thesis in the University of North Bengal titled ‘Muslims of Darjeeling Himalaya: Aspects of their Economy, Society, Culture and Identity’. In it he identifies four sections of Muslims in Darjeeling within which a prominent one is the Nepali Muslim. Due to this intimacy, an Nepali version of Urdu can also be heard.

In the year 2013, the first Urdu Diwan in the Nasta‘līq script called ‘Diwan-e-Maikash’ was published in Darjeeling, the author of which was Maikash Kohistani. Dr. Shabana Nasreen– Assistant Professor (Urdu Department), Lady Brabourne College, Kolkata– who is the editor of this book, states that Kohistani’s real name is S. M. Yasin– a retired teacher of St. Robert’s High School Darjeeling, he chose ‘Maikash Kohistani’ as his nom de plume.

Bijoy Kumar Rai,

Bodhikhim.

November 10, 2017.

Bijoy Kumar Rai is an Asst. Master in Darjeeling Government High School. He is an author and editor who has served as the Secretary of G.D.N.S (Gorkha Dukha Niwarak Sammelan).

The article has been translated and published with permission for Bijoy Kumar Rai, author of Urdu-Nepali Sabdakosh.