Darjeeling History Club

Cinchona cultivation in Darjeeling District started around 1861 – 1862. Sir Joseph Hooker sent the first cinchona seeds in 1861 to Dr. Thomas Anderson, the then Superintendent of the Calcutta Botanic Garden, who conducted all the cinchona experiments in Bengal until he left in 1869. In 1861, Government deputed him to inspect the cinchona plantations in Java, Indonesia. He received every assistance and attention from the authorities there, and brought back with him a large number of healthy plants. A few were retained for experiments in Bengal, and the rest he took to the nursery at Ootacamund, Tamil Nadu. Dr. Anderson suggested the establishment of a cinchona nursery in Darjeeling. The proposal was approved, and a site was selected near the summit of Senchal in the midst of dense forest.

The environment in Senchal proved too severe for cinchona, so in April, 1863, the plants were temporarily removed to a garden at Lebong, a comparatively warmer place. For a permanent plantation, Rangjo valley at Rangbi, 20 kms away from Darjeeling town, was found and decided. The Rangjo valley lay on the south eastern slope of a long spur, projecting from Senchal, at an elevation between 1,300 and 4,000 feet above the sea.

“the objective of the government was to supply the hospitals and the people with a cheap remedy for malarial fever”

L.S.S. O’Malley writes, “here the cultivation, on an extensive scale, of those species of cinchona which contain quinine and allied febrifuge alkaloids in their bark was begun in 1864. The plantation was started with one hundred plants each of Cinchona Succirubra and Cinchona Officinalis, and two plants of Cinchona Calisaya, at an elevation of about 4,000 feet. The stocks of plants rapidly increased, so that ten years after the inception of the undertaking, there were nearly three million trees in existence, mostly of Cinchona Succirubra, and the original clearing on the slope of the Rangbi had been extended in a south easterly direction to the Rishop and Mangpu ridges in the Rangjo valley, while new extensions, comprising in 1881 about 750 acres, had been opened at Labdah on the northern and Sitong on the southern slope of the Rayeng valley. For about the first decade the majority of the trees on the plantation were Cinchona Succirubra, the species which yields red bark, poor in quinine but rich in a mixture of febrifuge alkaloids allied to quinine. The remainder of the trees were mostly of Cinchona Calisaya, or Ledgeriana, as it is now called, the species yielding yellow bark, rich in quinine.”

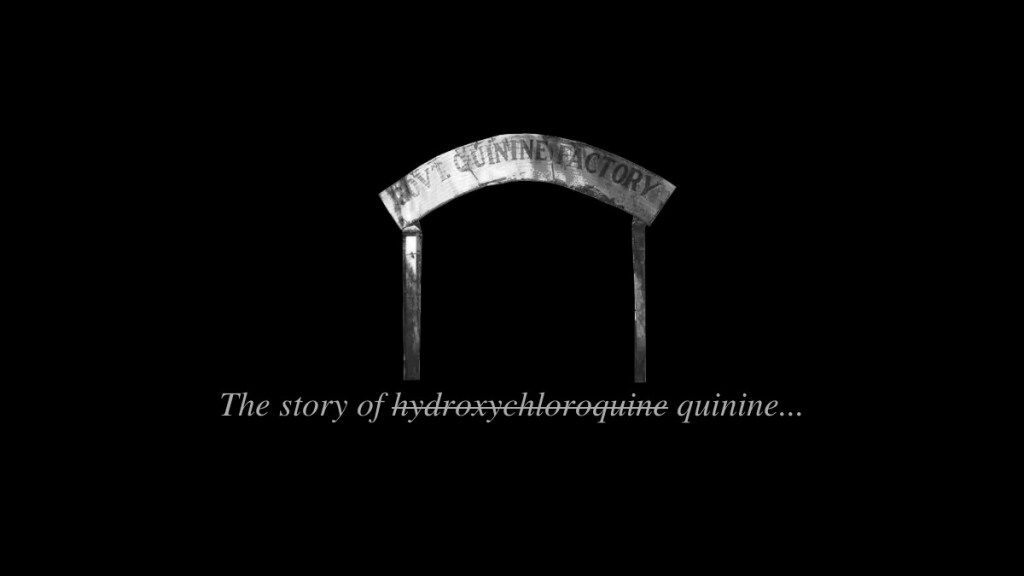

In 1868 – 70, Dr. Anderson submitted a proposal, for the manufacture of a cheap but powerful febrifuge (a medicine to reduce fever), well suited for use in native hospitals and charitable dispensaries at the Rangbi plantation. The purchase of machinery for the experiment was sanctioned, and as a result of which a factory was established at Mungpoo in connection with the Rangbi plantation. In 1874, the manufacture of Cinchona febrifuge was begun, and the first year’s working yielded about 50 pounds of febrifuge. Up until 1887, only Cinchona febrifuge was manufactured. In 1880, Dr. King, the then Superintendent, initiated the policy of converting the plantation from one in which red bark trees, poor in quinine, preponderated, into one of quinine yielding species. In following this policy, the yellow bark quinine yielding species, Cinchona Calisaya, was planted out in gradually increasing numbers. This substitution was pushed on with such vigour that beginning in 1880, there were 4,000,000 red bark trees to 500,000 yellow bark and hybrid trees together. And by the start of the the twentieth century, there were over two million yellow bark and hybrid trees to the 200,000 red bark trees.

By maintaining these plantations, the objective of the government was to supply the hospitals and the people with a cheap remedy for malarial fever. In 1887, the manufacture of sulphate of quinine was commenced in the Mangpoo factory by a process of extraction by fusel oil– a mixture of several alcohols produced as a by-product of alcoholic fermentation– elaborated by Mr. Wood, formerly Quintologist and Mr. Gammie, the Deputy Superintendent of the Plantations. From 1887 onwards the factory continued to produce, in addition to cinchona febrifuge, sulphate of quinine, in yearly increasing quantities. The factory was now extended, in order that, it may turn out in the future, a minimum of 20,000 pounds ( about 9,000 Kg ). The issue of sulphate of quinine in 1887 – 88 was about 250 lbs, in 1900 – 01, over 11,000 lbs, and in 1905 – 06, nearly 16,000 lbs. A new system was instituted in 1892. By this system, the sulphate of quinine was sold to the public through the post offices in small packets, containing 5 grains, at the price of one paise, so as to enable even the poorest native to purchase a dose of the drug.

The plantations in the Rangjo and Rayeng valleys proved too small as compared to the number of trees that were required to keep pace with the increasing demand for febrifuge and quinine. So, accordingly, in 1883, the first outlying plantation of 300 acres was started in the Ranjung valley in Kalimpong. But the rainfall here was too heavy to allow cinchona to be successfully grown, and the plantation was exhausted and finally given up in 1893. The Nimbong plantation of about 500 acres, also situated in the same tract, was purchased in 1893 from a private company. No extensions were attempted there, but the trees standing on the plantation as purchased were gradually used up, till in 1896, the last was taken up and the plantation abandoned. In 1899, a fresh extension of about 900 acres was commenced in the Damsong forest block, situated about 10 miles north east of Kalimpong, near the junction of the Rangpo and Teesta rivers on the borders of Sikkim. In this new block, which is known as the Munsong Division, there were about 500 acres under Cinchona Ledgerians, with about 1,200,000 plants.

“the sulphate of quinine was sold to the public through the post offices in small packets, containing 5 grains, at the price of one paise, so as to enable even the poorest native to purchase a dose of the drug”

During the year 1906, there were three main cinchona plantations. First, the Rangjo valley block, consisting of the Rangbi and Mungpoo divisions, which measured about 900 acres containing nearly over 2 million plants, of which more than a million and a half were Cinchona (Calisaya) Ledgeriana, nearly half a million of hybrid. The remainder was Cinchona Succirubra. Second, the Rayeng valley block, consisting of the Sitong and Labdah divisions, which together comprised an area of about 600 acres, with over 200,000 plants, more than half of which were Cinchona Succirubra and hybrid, and the remainder Cinchona (Calisaya) Ledgeriana. Third, the Rangpo valley block comprising of the Munsong division.

L.S.S. O’Malley writes–

“in appearance cinchona seed is small and chaff like, weighing 60,000 to 70,000 to an ounce. This is harvested during February and March, and at once sown in prepared beds, protected from the weather by thatched watertight lines, with sloping roofs constructed some 5 feet high in front and 2 feet high behind, and facing north to prevent sunshine drying up the seed beds. When half an inch high, the seedlings are replanted in other beds an inch apart, and later, when they have attained a height of 3 to 4 inches, they are again transplanted to other thatched nurseries similar to those prepared for seed beds, and near to the land to be planted out. By October the seedlings will have completed their first year’s growth and be a foot in height. The thatched covering of the lines is then removed and the seedlings hardened off by exposure to sun until February, March or April, when they are planted out in their permanent places in the land prepared for them. Once growing weather has set in, the young plantation for the first year is kept clear by hand-weeding about the plants and by sickling the intervening spaces. From the second year onward, weeds are kept down by repeated light hoeing and hand weeding. Barking operations are carried out equally throughout the whole year, and are first begun when the trees are three years of age. Thinning then becomes necessary wherever overcrowding exists, and individuals that show signs of unhealthiness are uprooted. Every year the whole plantation is thus gone over and trees removed where necessary. To collect bark, the trees are uprooted and divided into three parts – root, stem and branch. All the bark is completely scraped off with blunt knives, and the three kinds – root, stem and branch – dried in open air sheds, or in a heated go down during wet weather. Each kind is stored separately, and they are then taken for the extraction of the alkaloids to the quinine factory.”

The most extensively grown species was Cinchona Ledgeriana. Previously, a hybrid between Cinchona Succirubra and Cinchona Officinalis was grown largely, but it was replaced by another hybrid between Cinchona Succirubra and Cinchona Ledgeriana, which was raised at Mungpoo. From Mungpoo, selected trees yielding a minimum equal to 5 percent quinine sulphate were set aside for future plantations.

Regarding the preparation of cinchona febrifuge ( a medicine used to reduce fever ), L.S.S. O’Malley writes–

“the dry cinchona bark is first mixed with slaked lime and ground to a fine powder. It is then moistened and tipped into vats containing dilute caustic soda solution, which is heated by a steam coil lining each vat and continually stirred by a mechanical arrangement. Oil is then run on to the homogeneous mixture, the stirring kept up for two hours, and afterwards the whole allowed to stand till the oil has again separated completely from the bark sludge, carrying with it most of the quinine in solution. The remainder of the quinine is extracted by repeating the stirring with a second quantity of oil. The oil layers are run off from the top of the exhausted bark, and in another vat are stirred with water and sulphuric acid, which extracts the quinine and leaves the oil ready to be used again on more bark. The excess of acid in the aqueous quinine solution is then neutralized, and the crude quinine sulphate separates out as a crystalline powder. It is purified from the other cinchona alkaloids by recrystallization from water, and from coloring matter by the aid of precipitants. The liquors from which quinine sulphate has been obtained are still saturated with it, and also contain all other alkaloids from the bark. They are mixed to give a product of definite composition, coloring matter is removed, and then all the alkaloids are precipitated together by addition of caustic soda. This mixture of alkaloids after washing, drying and powdering constitutes cinchona febrifuge.”

The article was provided by the Darjeeling History Club.